A great article by Kenan Malik removing the sanctified coat and presenting a raw human Muhammad Ali of Jim Crow era. ” I am America. I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me. Black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own; get used to Me” posted by f.sheikh.

‘A strange fate befell Muhammad Ali in the 1990s’, Mike Marqusee writes in Redemption Song, his wonderful, illuminating study of ‘Muhammad Ali and the Spirit of the Sixties’. ‘The man who had defied the American establishment was taken into its bosom. There he was lavished with an affection which had been strikingly absent thirty years before, when for several years he reigned unchallenged as the most reviled figure in the history of American sports.’

The global outpouring of grief, affection and tribute to Ali this weekend has been moving and heart-warming. Yet, there is a part of me that thinks that, as affection has washed away the old contempt with which he once was greeted by large sections, especially of American society, we have also lost something of the sense of Ali’s true greatness. It is not that I would rather that Ali be treated with contempt than with affection – far from it. Nor is it that Ali’s brashness and braggadocio, his opposition to the Vietnam War, or his support for the Nation of Islam, have been ignored in the thousands of eulogies this weekend. It is rather that, as Ali’s biographer Thomas Hauser observed, so much effort has been spent trying to sanitise Ali that we are danger of forgetting the real man and his real courage. It is also that we have moved so far from the world that created Muhammad Ali that it is difficult properly to comprehend the hatred and revulsion that once greeted him, or the radicalism and hope that he embodied.

There is a danger, too, of sanctifying Ali, of according him mythical status, and so depriving him of his real humanity. He was a man of great contradictions and, like all human beings, of deep flaws. He was one of the greatest symbols of black pride, and yet, as Arthur Ashe said of his run-ins with Sonny Liston and Floyd Paterson, ‘No black athlete had ever spoken so disparagingly to another black athlete’. He was proud of his accomplishments as a fighter, and yet also deeply ambivalent about his role in the ring, describing boxing as ‘a lot of white men watching two black men beat each other up’. He was an icon of the civil rights movement yet pledged allegiance to the Nation of Islam, an organization that despised the movement and the ‘integration agenda’. He prized friendship and loyalty, yet treated his friend and mentor Malcolm X with cruel disdain after the latter broke with the Nation of Islam.

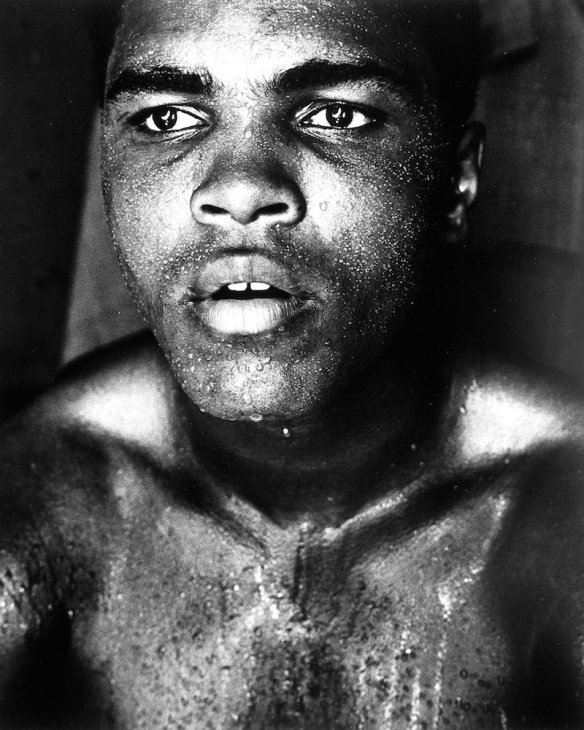

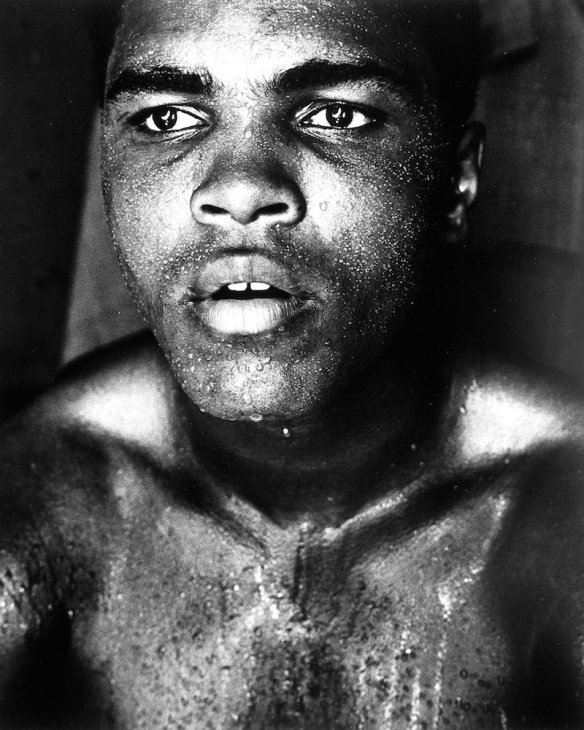

Part of Ali’s greatness, however, was his ability to reveal all his contradictions and flaws, and yet also to transcend them. Listening now, in an age which most boxers are merely loudmouth journeymen, to Ali’s great, boastful tirades, the ‘Louisville Lip’ may sound similarly tiresome. But that is not to understand the context of his swagger. In an age of Jim Crow laws and brutal lynchings, for a young black man to stand up and proclaim his greatness, defy convention, refuse to be humble or to know his place, was an incomparable act of bravery and defiance. It was a means of turning the world on its head, of demonstrating that through strength of will and force of personality, it was possible to force people to look upon the world – to look upon you – differently. As Ali put it:

I am America. I am the part you won’t recognize. But get used to me. Black, confident, cocky; my name, not yours; my religion, not yours; my goals, my own; get used to me.

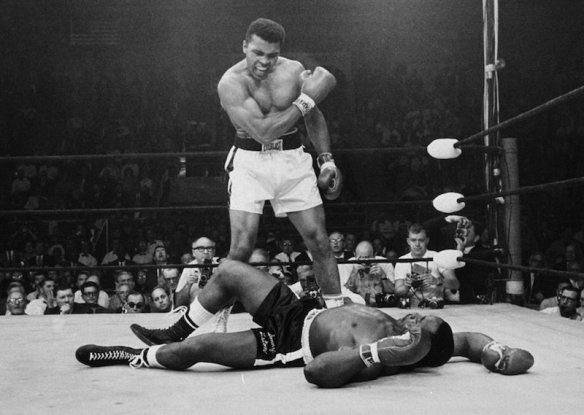

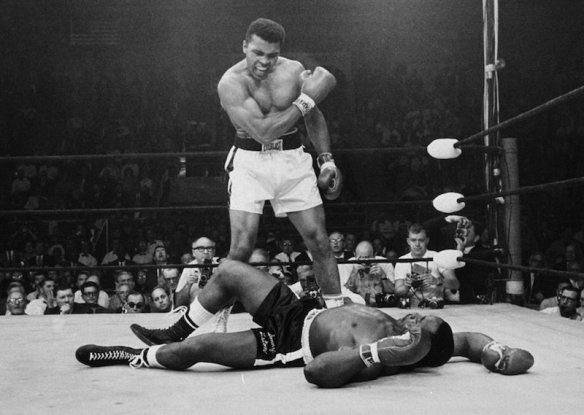

Ali’s support for the reactionary National of Islam may, from today’s perspective, seem disturbing. But, again, in the context of the treatment of African Americans in the 1960s, it was a bold insistence on being able to define his own identity, and not allowing himself to be constrained by a deeply racist society and by his ‘slave name’. The day after he defeated Sonny Liston to become world champion for the first time, Ali held a press conference in which he formally announced that he had joined the Nation of Islam (he had secretly been a member for two years). ‘I don’t have to be what you want me to be’, he told the assembled media. ‘I’m free to be what I want.’ ‘I don’t have to be what you want me to be’. Nothing better summed up the Muhammad Ali of the 1960s, or why he drew upon himself such opprobrium and contempt from the establishment, or why, for so many, he was such a symbol of aspiration and hope.

Ali’s refusal of the draft to fight in Vietnam was a courageous stance. His willingness to stand by his decision, despite the authorities stripping him of his world title, his boxing licence, his passport and almost his liberty (he was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment for draft evasion, the conviction eventually being overturned by the Supreme Court after a four-year legal battle), was an act of great principle. ‘Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?’ he asked. ‘The real enemy of my people’, he continued, ‘is right here. I will not disgrace my religion, my people or myself by becoming a tool to enslave those who are fighting for their own justice, freedom and equality’.

Click here for full article